“It must have been my lucky day,” Lakpa Sherpa says, encapsulating the miracle his family performed to secure his exit from Nepal during its recent, bloody civil war.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, a Maoist communist insurgency faction fought to topple Nepal’s 240-year-old monarchy. Most members of the royal family were massacred and the ensuing decade-long conflict witnessed summary executions, purges, kidnappings, and other war crimes.

Eventually, the monarchy abdicated and the Maoists established a people’s republic; however, governance has stagnated amidst infighting and widespread corruption. Officials struggle to bring prosperity where a strict caste system determines every aspect of a person’s life. Each of Nepal’s 134 castes mandate particular clothes, customs, family names, plus occupation and marriage restrictions. Each caste also speaks its own language.

Contrary to popular misconceptions, although his last name is Sherpa, Lakpa was never a mountaineering guide hauling gear up and down the Himalayas for Western adventurers. “Sherpa” only recently acquired that connotation. Historically in Nepal, Sherpa designated a particular ethnic group living primarily in the remote, high mountain regions.

Children born into the Sherpa caste are commonly named for days of the week—more accurately, for the deity protecting that day. For example, Pasang translates to Friday. Lakpa’s day is Wednesday.

Lakpa’s family suffered persecution because they formerly supported the monarchy. The new regime wanted a guarantee of their loyalty which could come in the form of a pledge. The Sherpas could pledge money or send a family member away to learn proper Maoist philosophies.

As soon as all the travel documents were in place, Lakpa left Nepal in 2010. He eventually wound up in the U.S. when the government granted him political asylum.

“People say America is the human rights country. How you call it? On the top?” he says. “I come here to the land of opportunity. Everything is freedom here.”

In his pursuit of freedom, Lakpa discovered a bizarre world with a baffling culture. For instance, electricity flowed all day, instead of the half hour he was used to back in Nepal. Also, eateries offered a dizzying variety of food options. Choosing a bread at Subway was initially daunting.

Lakpa secured work initially at his uncle’s restaurant, the Himalayan Kitchen on Durango’s Main Avenue. He also enrolled in English-as-Second-Language (ESL) classes at the Durango Adult Education Center. Back in Nepal, he’d attended a boarding school where they taught British English.

“Lakpa works really hard,” says Sarah Brown, Lead ESL Teacher at the DAEC, in praise of her student. “He really puts in the time. He comes to class all the time.”

Students in an ESL class are usually immersed in the English language. Instructors start off using lots of gestures, pantomimes, and videos to communicate meaning. They do not resort to word-for-word translations; indeed, how could they when each student may come from a different country with a different language?

After 14 years of teaching ESL, Sarah has seen the DAEC classroom function as its own community builder. “I feel like it can be very isolating when you don’t speak much English. You just stick with your [language] community. Our ESL students get to know other people who are kind of in the same situation as them.” As the students struggle together, eat together, and learn to converse in English together, their judgments, and stereotypes break down and some remain friends forever.

Beyond the social circle, ESL classes integrate students into the broader community. As they gain confidence in their communication skills, they are more likely to find better jobs, expand their activities, serve on committees, or volunteer at their children’s schools.

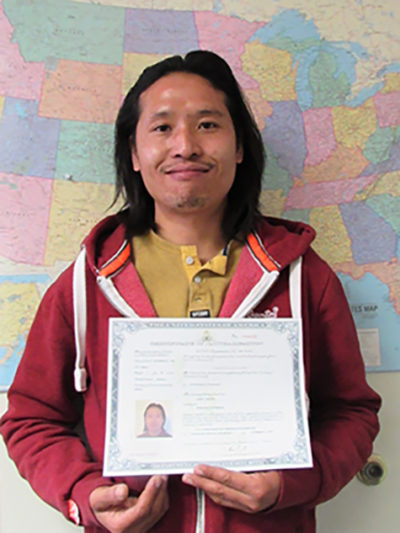

Lakpa holding his US citizenship certificate

Lakpa has certainly improved his employment prospects over time, moving from the family-owned restaurant to full-time custodial work at Fort Lewis College. He hopes to launch his own business one day and recently brought that dream closer to reality when, in October, he was granted U.S. citizenship.

Citizenship candidates must prepare for the Naturalization test, which includes reading and writing tests, as well as an oral civics test and costs $725. Candidates study about U.S. government and history and must complete an interview with an immigration officer wherein they showcase their English comprehension and communication skills.

The DAEC teamed Lakpa with Marie Roessler, a volunteer tutor specializing in citizenship preparations. As a child, Marie emigrated from Europe to the U.S. in the 1950s. She knows the process not only front-to-back, but also firsthand. While working with Lakpa, she focused on the written portion of the test.

Now an official U.S. citizen, Lakpa jokes, “No more paperwork! Everything is easy now!” Turning more serious, he says, “I am very happy now. I am here ultimately. If anything happens, I am here. I am free!”

He goes on to say that he is grateful for all the people who helped him begin a new life so far from home. He is glad he came to a friendly and welcoming town. He is grateful for the ESL classes and his citizenship tutor. As a result, whenever anyone asks him for help, he does not refuse.

Going forward, he plans to follow the advice from a close friend who told him, “Lakpa, if you want your life better, you have to be Eastern heart and Western mind.” Lakpa unpacks the expression this way: keep your family always in your heart and your plans always in your thoughts. For him, that practice makes every day his lucky day.

For more information about the Durango Adult Education Center’s ESL or Citizenship programs, please visit: www.durangoadulted.org or call 970.385.4354.